The Transit of Mercury May 9 2016

The transit of Mercury took place on May 9 2016 and was observed by me at my home in Helsby, Cheshire, U.K., where I had previously observed the transit of Venus in 2004. Unlike that particular event, the transit of Mercury is a relatively frequent event, occurring thirteen times every century. Nevertheless it was rare enough to merit a special effort to record it photographically. The transit was predicted to start at 12:12 BST and end at 19:42 BST. I spent the morning setting up my telescopes and cameras beneath clear and sunny skies with only drifting cirrus clouds threatening to interfere with the event. I was optimistic that I would see a significant part of the transit and possibly the whole of it.

My telescopes consisted of an equatorially mounted Meade LX10 (which I had used to observe the 2004 transit of Venus), with a piggybacked William Optics Megrez 72 refractor. I also had a separate Coronado Personal Solar Telescope (PST) equatorially mounted on a Skywatcher Star Adventurer. The LX10 had a metal-on-glass sun filter (also a 2004 veteran), which gave the Sun image an orange colour, and the Megrez 72 employed a filter constructed from Baader solar film, which gave a blue-white image. The PST required no filter and gave a typically red image of the Sun.

My two cameras were both Nikon D40 DSLRs, which I often use for astro-photography. Camera 1 was devoted to afocal projection using a 50mm camera lens and a 26mm Plossl eyepiece with both the LX10 and the PST. All photographs taken were Normal JPEGs at ISO 200. Camera 2 was used exclusively for focal plane imaging with the Megrez 72 in raw NEF format, again at ISO 200. I intended that Camera 2 should provide a definitive record of the transit and for that purpose I took 4 rapid shots of every image for subsequent stacking. The Camera 1 shots were more opportunistic and informal; I wanted to see if afocal projection could provide decent images, particularly with the PST, which had previously proved difficult to use for imaging.

I first observed Mercury on the surface of the Sun at 12:13:14 BST (timed using a radio controlled clock). It was just on the Sun's limb, but not at the predicted time. Whether this was due to local differences or inadequate attention on my part I couldn't say. Photography commenced in earnest thereafter.

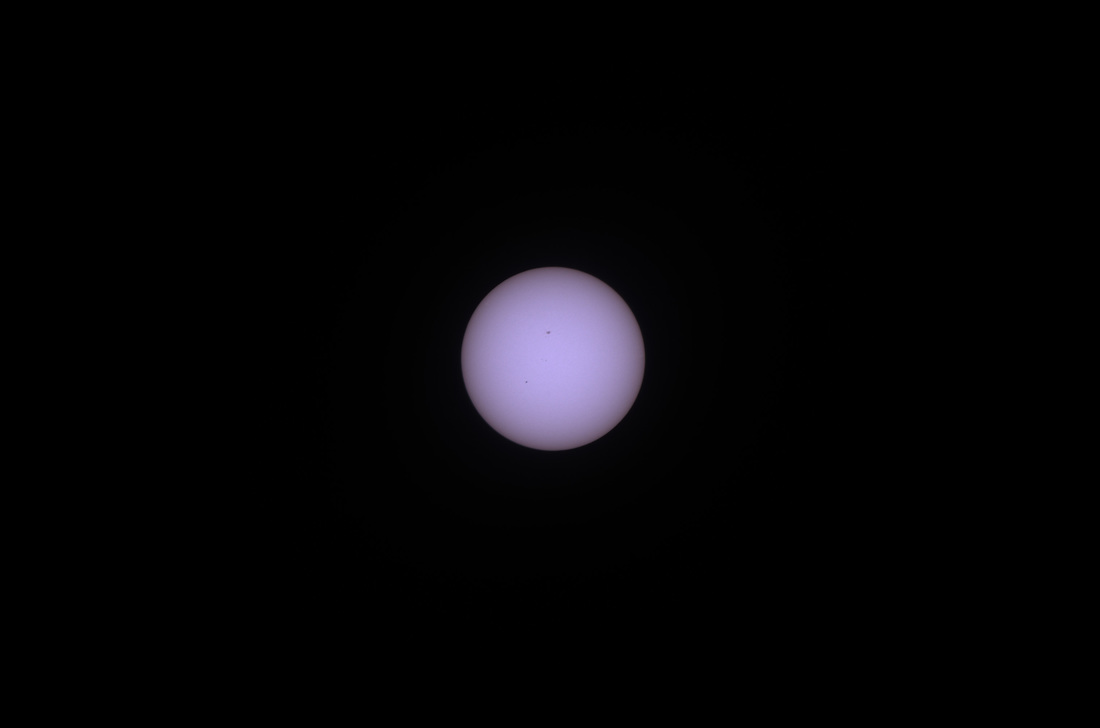

So how did things pan out? Well, using afocal projection (Camera 1), the PST still proved to be a difficult telescope to get good pictures from. I managed a few reasonable ones, with Mercury visible against the Sun's disk, but I found it hard to get the details of the Sun's surface to show clearly. The details could be seen with the eye looking through the eyepiece, (though not as clearly as I believe they should despite a long time fiddling with the echelon fine tuner and the focus knob). Furthermore, the details I did manage to see with my eye did not stand out in the shots. I clearly have some things to learn here! However, here is a typical example of one of my better shots (look closely!).

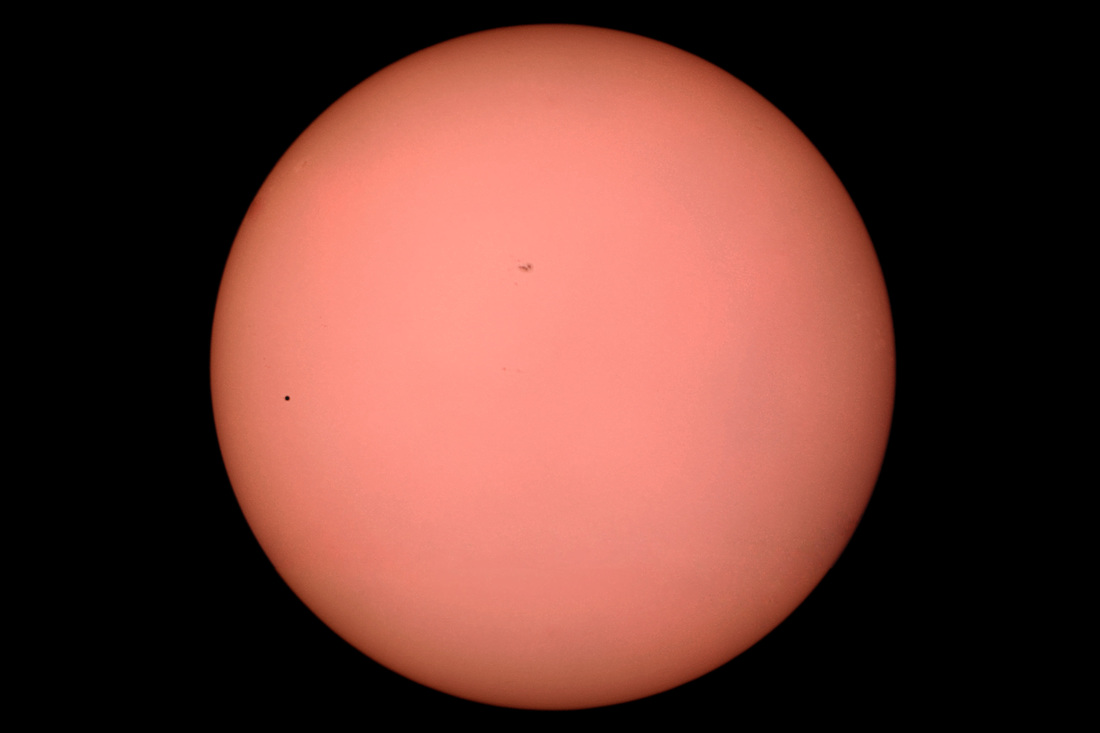

Taking pictures with the LX10 using Camera 1, was a great deal easier. All I had to do was ensure the picture was in focus, which was easy. The image of Mercury was x5 larger than for the PST (with the same eyepiece) due to the longer focal length of LX10. Unfortunately, this meant the solar image was too large to be completely captured by the sensor of the camera and I did not have a longer focus eyepiece to offset this. Also the Sun's surface did not reveal any great detail, apart from a few sunspots. This was turned to advantage in the following shot, where the bottom quarter of the Sun was easily reconstructed from the top quarter of the disc to make a full representation. Note this did not interfere with the image of Mercury, which remains an accurate rendition. The overall result is quite pleasing.

The pictures taken with Camera 2 in the focal plane of the Megrez 72, encountered a few problems. It proved quite difficult to focus accurately on the Sun's disc, which was not particularly large on the sensor. It turned out that the real source of the problem was the high cirrus cloud which was prevalent when the transit began and also later on when it thickened to the point of rendering Mercury invisible (and led to an early finish of the session). At various points in the transit the cloud sometimes interfered and sometimes did not. Before every set of 4 shots I tried to refocus manually to get the best image, but it is evident from the series of 212 shots I took overall, that I did not always succeed. In the end maybe 50% of the shots were reasonably good. These were combined in groups of 4 to get a decent set of final images. Unsharp masking was employed to improve the remainder. Some example images appear below.

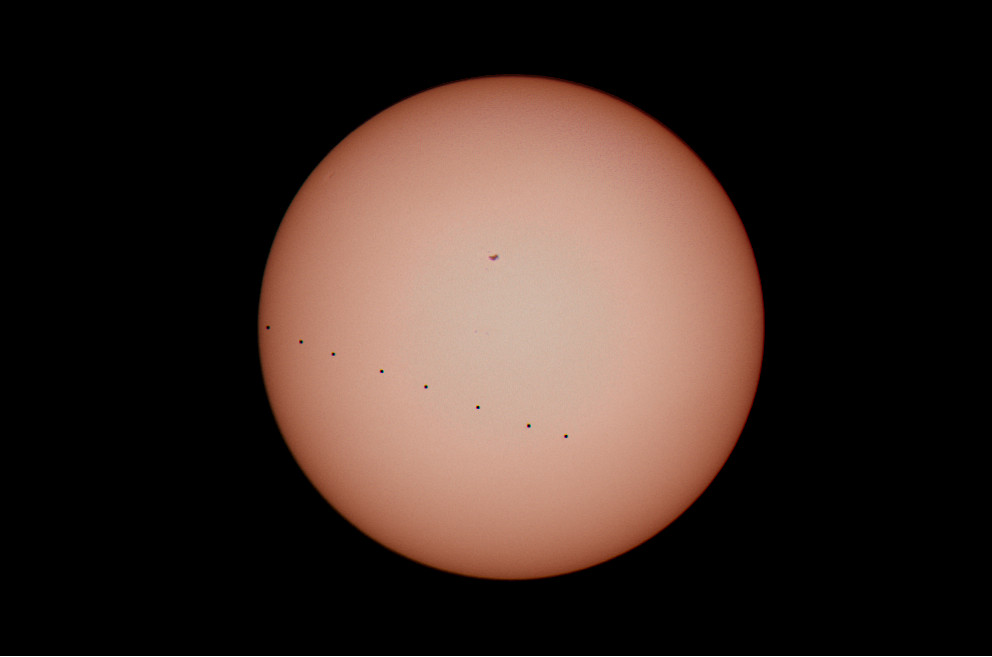

An obvious thing to do with multiple images of a transit is to combine them to show the transit progressing through various stages. In principle these should lay out the planet images in a straight line across the Sun's disc. While doing this I discovered that the camera orientation was subject to small, random changes, due to some play in the T-ring lock and also the slightly different focus of individual pictures meant the Sun's disc was not always precisely the same size! For this reason I chose only those images that were well focussed and appeared to follow a reasonable straight line. The result is shown below, where the line of images of Mercury is a little erratic, but shows its progress across the disc quite well. Given the problems, the result is quite nice. (Note the colour of the Sun's disc has been changed to a more pleasant hue.)